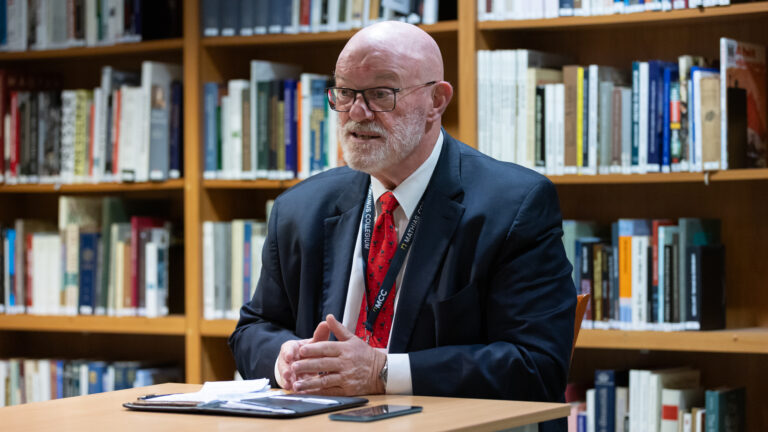

Ferenc Kumin has been serving as the Hungarian Ambassador to the United Kingdom since 2020. He has a PhD in political science from the Budapest University of Economic Sciences. This month, Ambassador Kumin travelled back to Budapest, Hungary, to take part in an event honouring British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, hosted by the Danube Institute. He was also kind enough to give an exclusive interview to our website.

***

We are here at a Danube Institute conference honouring the life and legacy of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher of the United Kingdom. She has a pretty special place in Hungarian history, too—I don’t know if you agree. How do you see, as a Hungarian, her legacy on the world stage?

I think that every politician—and every important and powerful politician like her—has at least two different approaches: the international persona and the domestic persona. And it’s, of course, a different perspective for anyone within the UK, how they view her, because there, she is considered to be a conservative hero. And of course, her legacy appeals to many others beyond just the followers of conservative thinking. Nevertheless, she is viewed through the lenses of political denominations.

But for us, and for the rest of the world, I would say she is considered a hero regardless of political denomination or political view. This is especially true for the peoples of Central Europe—and very rightly so. Here I, of course, refer to the great title of the excellent book by John O’Sullivan, The President, the Pope, and the Prime Minister: Three Who Changed the World.

This triangle of heroes of the regime changes in Central Europe is, I think, the best way to point to the people who played the most important role. And just as a footnote to that: in Budapest, we already have statues and memorials for two out of the three. We have a statue of Ronald Reagan. We have several sites honouring Pope John Paul II. So, it was high time to have something for Margaret Thatcher as well—and this is a perfectly fitting time and moment to do that, as her 100th birthday is approaching.

The United Kingdom is a peculiar country for conservatives, because there was a succession of four elections in a row that the Conservative Party won between 2010 and 2019. Yet British culture isn’t as conservative as this might suggest—or as conservative as, for example, Hungary or Poland. Do you think there’s a kind of disconnect between the party leadership and the more socially conservative movement?

Well, it’s a difficult question. I would say that, of course, to have a real hero like Margaret Thatcher, you need to go beyond political denomination. You need to be a leader with decisions, with challenges, with actual achievements that transcend any single political family, so to speak.

As we’ve heard at the conference—and I couldn’t agree more—there is the opportunity, and there are the persons. And Margaret Thatcher’s case was that very fortunate meeting of opportunity and person. At the right time, the right person was there, ready to take up the challenge.

I don’t want to go into today’s affairs, as it’s not my job to assess anything that concerns the current affairs of my wonderful, wonderful host country, the United Kingdom. But her memory definitely shines through, and the 100th anniversary of Margaret Thatcher’s birth is something remarkable in the UK’s public sphere. Articles have already appeared in various newspapers, and as her birthday approaches, it’s going to become more and more prevalent.

Before Brexit, when the United Kingdom was moving toward an exit from the European Union, was there a certain level of camaraderie in scepticism between the Hungarian government and the British government—a sort of shared Euroscepticism? Evidently, Hungary is not planning to leave the EU, but was there some common ground in opposition to Brussels at the time?

I would say yes, of course. It’s no secret that Hungary viewed the decision of the British electorate back in 2016 as an outcome we were not happy to see. Nevertheless, we understood their reasons. And after the decision was made, our position was, of course, to respect it—as we do with all democratically made decisions.

But before Brexit, the United Kingdom was certainly an ally of Hungary within the bloc. We shared many, many views when it came to the sovereignty of our nation—the sovereignty of Member States within the EU. In that particular respect, we lost an ally with Brexit.

Also, every single time we have the opportunity, we say that the entire bloc lost an important player—in terms of economics, defence capabilities, and more. So it's something everyone needs to reflect on and try to understand, both the consequences and the reasons behind it. We always try to urge our fellow Member States, and the leaders of various European institutions, to keep an eye on what went wrong with the UK—and whether there are lessons to be learned from that experience.

Let’s get back to Prime Minister Thatcher. What significance did her visit to Budapest in 1984 have in the ultimate collapse of the Soviet Union? Some of the speakers here have made the case that it was an important catalytic event. Was it really that significant?

The 1984 visit was more significant than anyone might imagine today. It’s something I can personally relate to in a strange way, because I was nine at the time. But even as a nine-year-old, I have some memories of watching the news and listening to the conversations around me—how amazed everyone in Hungary was to see the British Prime Minister behind the Iron Curtain, at a time when no real hope for change existed.

Probably the first winds of change had begun to blow around then, but they weren’t taken very seriously yet. Having her as an official guest was obviously seen as a good sign. But what mattered even more was that, up until that time, the communist regimes—Hungary’s included, but others as well—had tried to portray Western leaders as dangerous, as evil people who only wanted to wage war against the Eastern Bloc. Then suddenly, we had this very well-known, very characteristic Western leader visiting Hungary—specifically Budapest—and walking around like a normal human being. That had a real impact.

Ferenc Kumin on X (formerly Twitter): "It's been my privilege to welcome Sir Mark Thatcher, the son of the late Prime Minister and discuss important and timely aspects of his mother's memory in Hungary. pic.twitter.com/T5p2oIA9e6 / X"

It's been my privilege to welcome Sir Mark Thatcher, the son of the late Prime Minister and discuss important and timely aspects of his mother's memory in Hungary. pic.twitter.com/T5p2oIA9e6

And of course, the Great Market Hall visit was key to these memories. She had a very packed schedule. She only spent probably two days here, if I’m not mistaken. Somehow, they managed to squeeze in this visit. Today we would call it a soft programme, probably between meetings with the leaders of the Hungarian government and the communist regime. And all the pictures that we remember today were taken at the shopping ground in the Great Market Hall. I had the good fortune to just search a little bit for this occasion about this visit, and there is plenty of very good material out there on the internet, on the Margaret Thatcher Foundation’s website.

And I found a speech where she mentioned her visit a couple of years later in a Hungary-themed gathering. She was talking about the Great Market Hall experience herself as well. First of all, it was good for me to realize that it wasn’t just a big experience for us who were watching it on the news, and it just burned into our retina, this picture of her shopping for garlic, honey, paprika, and the rest. But it was important for her as well, because a couple of years later, she referred back to this experience, saying that at the Great Market Place, she realized that these people, the Hungarians, were market-savvy people because she could feel around her that they knew what the market was and they knew what the value of their products was. And she had the conclusion—we’re talking about 1984, a long time before the eventual change of regime—that the roots of the market economy were present in Hungary, and consequently, Hungary was ready for it by that time.

And I guess this is a marvellous observation, not only because it turned out to be true, but also because it just reflects on her very down-to-earth approach of how to look at people, how to gain insight, and learn from first-hand experiences. It is something that today’s politicians would like to be like. But we’re talking about the 80s, when it wasn’t that much of an inevitable thing that politicians just walk around for a good photo opportunity or organize one. It was really, really special for her, and probably the most important memory of the transitional Hungarian years.

Did she take a risk by visiting Hungary at that time? Was there any chance that her visit could have backfired on the global stage?

Yes, very much so. If you look at the literature and all the documents that are now revealed—some of them were secret documents that are now declassified, and we can read and study them—you can tell through those documents that, yes, indeed, it was considered to be a risk. After all, Budapest, Hungary, was considered to be part of the outer empire of the Soviet Union. The Cold War was raging at the time. I should say we’d just been over the worst period of it; we were on the brink of a nuclear clash just a year earlier than that. So in that sense, it was a lot of risk for her. There were a lot of personal aspects. Why Hungary? Because she could have visited Prague or Warsaw. There were reasons why she did not choose Warsaw; there’s a whole line of literature about that. Martial law was in place in Poland at the time, so it would not have been a good choice.

Hungary was considered the most joyous barrack and thus a good destination, but there was also a very personal aspect: the UK ambassador in Budapest at the time was Bryan Cartledge, who before his appointment had been a personal assistant to Margaret Thatcher. Someone she knew very well and stayed in close contact with. Bryan Cartledge was able to work on the visit and convince her to come, which played an important role in putting together this very risky business.

It was unusual for the Hungarian side too, as they weren’t accustomed to receiving Western leaders. Diplomacy then mostly involved visitors from the Eastern Bloc and Warsaw Pact countries. So it was special for both sides, but it eventually worked out well. Of course, it was also a sign of the times: Hungary was on the verge of bankruptcy, running out of funds. They knew that they needed to somehow cosy up to the West as well, and this was a good opportunity for that.

Related articles: