The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), Japan’s current and longtime ruling party, has selected Sanae Takaichi as its new party leader and is set to become the country’s first female Prime Minister in its history. While that in itself is a historic milestone, Takaichi’s selection as the new leader of the LDP party will have several long-lasting effects on not just Japan, but the Japanese–European and Japanese–Hungarian relationship for years to come.

Described as a protégé of late former LDP party head and Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, Takaichi is speculated to continue Abe’s policies of continued tax cuts and higher spending. A staunch conservative and nationalist, when it comes to matters of foreign policy, Takaichi is expected to seek stronger ties with the United States and Europe. A regular visitor to the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo (the controversial shrine which honors the fallen Japanese soldiers, and even convicted war criminals from WW2) and staunch defender of Taiwan, it is unlikely that the Japanese–Chinese relationship will grow under her leadership. On the contrary, Takaichi has been described as being more hawkish towards the CCP and has even publicly proposed entering into security agreements with Taiwan.

Amongst this backdrop, the soon-to-be PM of Japan is likely to double down on work to grow Japan’s relationship with Central and Eastern Europe, including Hungary. As a former economic security minister, trade is expected to be high up on Takaichi’s to-do list once she assumes office on 15 October. While she has stated that she will not try to revisit or renegotiate the current trade deal her predecessor signed with President Trump, she is expected to take measures to mitigate the pain Japanese companies are starting to feel as President Trump’s tariffs take effect.

‘The soon-to-be PM of Japan is likely to double down on work to grow Japan’s relationship with Central and Eastern Europe, including Hungary’

Even if Takaichi is unlikely to friend-shore over security, there is a real possibility that she will over trade. Hungary, already home to over 180 Japanese manufacturing firms, including automotive giants such as Suzuki and Toyota, is in a prime position to receive increased Japanese investment and serve as Japan’s primary gateway to Central Europe. Coupled with Japan’s recent decision to synchronize its defense industry with that of NATO’s, Hungary is well-positioned to be a hub for new Japanese military technologies intended for European allies. With Hungary’s growing EV and electronic component production capabilities, the country has made itself an ideal location for Asian firms—particularly from Japan—to manufacture goods destined for European markets.

Beyond the automotive and electrical component manufacturing it offers, Hungary may hold the key to one of the most significant problems threatening Japan’s survival: its rapidly declining birthrate and aging population. It’s no secret that Japan is facing a demographic crisis of epic proportions. Many young people are choosing to remain single, not marry, and not have children. At the same time, cultural expectations place the burden of elder care on the younger generation. As a result, increasing numbers of young workers are leaving the workforce to care for aging parents.

This vicious cycle has led to a workforce shrinkage so severe that, for the first time, foreigners now hold as many as 2.3 million jobs in Japan. The crisis has forced Japan to experiment with new policies aimed at encouraging Japanese citizens to have children. To date, these solutions have been unsuccessful, but Hungary may offer Japan the guidance it needs to turn its ship around.

‘While imperfect, Hungary’s model offers Japan a valuable roadmap that could potentially help it begin to recover from the crisis it faces’

Hungary, unlike the majority of the Western world, has taken proactive steps to address its shrinking population dilemma, which has placed it in a significantly better position compared to its neighbors. Focusing on the problems facing the modern family, Hungary has been working to incentivize young Hungarians to marry and have children. From offering low cost government loans with interest rates of only 3 per cent to newlywed couples to help them purchase their first home, to providing tax incentives to systematically reduce the income tax of women who have children (the more children they have, the lower the tax, with a total elimination of all income taxes on women who have three or more children), the Hungarian government has managed to fare far better than the majority of industrialized nations when it comes to negative birth rates.

While imperfect, Hungary’s model offers Japan a valuable roadmap that could potentially help it begin to recover from the crisis it faces. Couple this with the similar traditional attitudes typically shared by Hungarians and Takaichi, the chance for the growth of Hungarian–Japanese cultural and soft power ties can be expected to increase under her leadership.

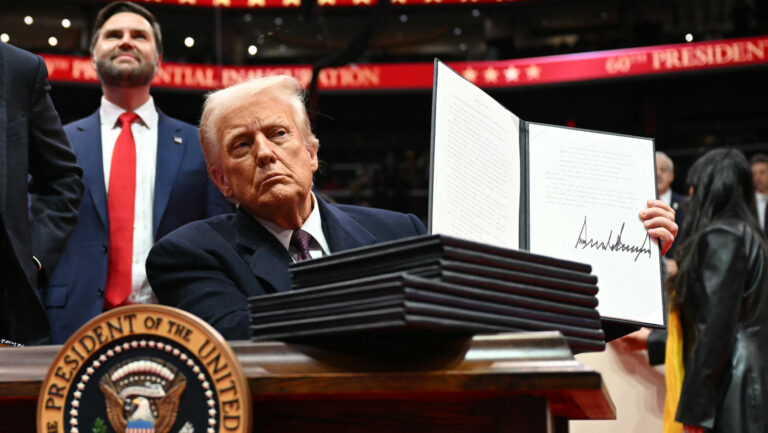

The potential for positive increases in the Hungarian–Japanese relationship is very real under Takaichi as Prime Minister, but only time will tell. As she prepares to be confirmed by the Parliament as PM next week, the largest item on her to-do list will be preparing for President Trump’s visit to Tokyo this upcoming 27 October. Takaichi has inherited a longlist of problems facing her country. The world will wait to see if she truly is Japan’s version of the Iron Lady and is ready to tackle them head-on.

Related articles: