This article was originally published in Vol. 5 No. 2 of our print edition.

A Review of Israel Alone by Bernard-Henri Lévy (2024)

Post-October 7 is an odd time for fealty probes among Israel’s professed backers, neutered as they seem to be by the cohering effect of reawakened life instincts. Yet, as is typical of victory’s uncertain measurement, it is by no means fully settled when a decisive win on the battlefield will return the Jewish state’s fate from windowless security troikas to the non-martial ‘war rooms’ of political metaphor. When it does, the deeper cleavages on which Zionism’s post-war future shall hinge will not appear unheralded. Shrouded beneath the imperative of victory lie several contests demanding scrutiny.

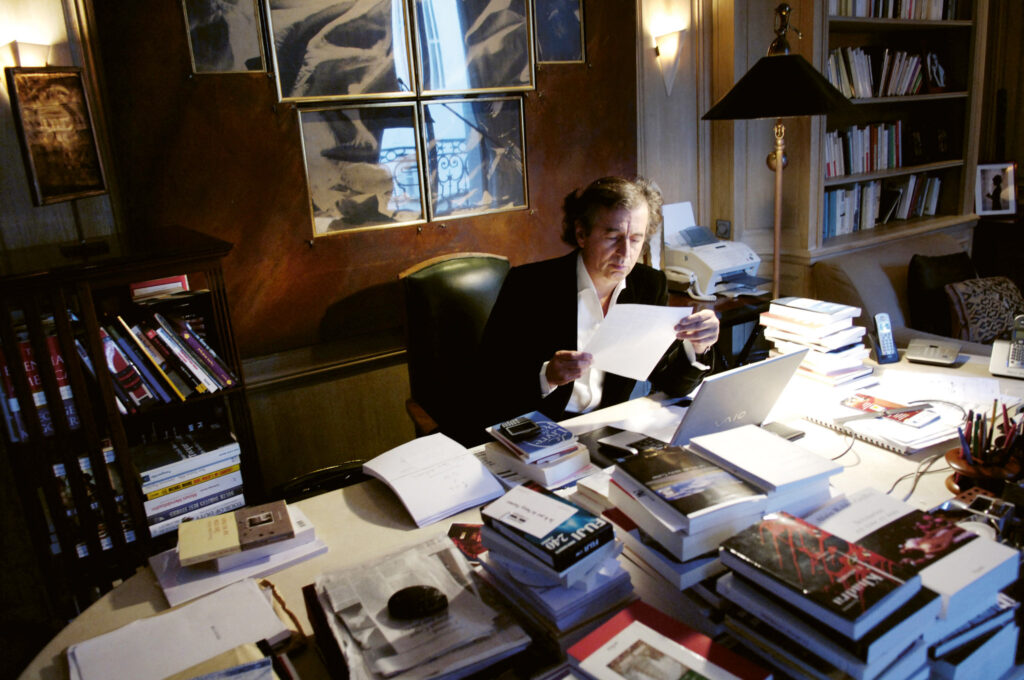

Bernard-Henri Lévy’s reputation for trading philosophical rigour for expediency is manifest in a confounding lack of subtitle to his wartime opuscule, Israel Alone published in December 2024.1 The Frenchman views the Jewish state as ominously torn, compounding the abandonment that focuses the book’s less original pathos. Israel is caught—écartelé (quartered) in the more gruesome French—between factions united by the exigencies of war, yet harbouring irreconcilable visions for the day after. The sovereign entity they closed ranks around thus appears a coveted trophy for rival ideologies.

Lévy locates the wrangling that routinely marks Judaism’s ethics of warfare not in the strategies adopted in Gaza and Lebanon, but in the domestic endgames sought by each faction. This inverts the ‘just war theory’ account of Israel’s divisions: the martial means it brings to bear, elsewhere grounds for charges of genocide and arrest warrants, are not up for debate; it is the post-war scenarios its constituencies pursue that arouse in Lévy excruciating moral anguish. His appeal to motives will otherwise strike many as odious. He suspects that those who rallied to Israel’s defence only in the aftermath of the pogrom harbour unsavoury motives, not least an imperfectly sublimated antisemitism that shields the West behind Jews as a moral token against the new Islamic face of non-Western alterity. Israelis submitting their state to ‘post’—or indeed ‘il’—liberal experiments, for their part, are accused of betraying Jewish values.

Common to the anti-Zionist left and Lévy’s liberal Zionism alike, this cynical depiction of the ‘new right’s’ rapport with Israel is as trite as it is disorienting for Israel’s sincere new friends. The French would call it a procès d’intention, an ad hominem refusal to engage with a substantial case by speculating on unfalsifiable ulterior motives. Yet it unveils a coalitional calculus that Lévy tallies up in stark terms, and that risks erupting, when guns fall silent, into fuller view than was the case before the war.

Granted, Lévy deserves credit for standing between a war he deems just and ‘pro-Israel’ liberals abhorring the state’s present rulers. The latter’s calls for ceasefires stem from dilemmas around rescuing hostages and defeating Hamas militants, but also from the prospect of toppling Prime Minister Benjamin (Bibi) Netanyahu—or a combination thereof. Lévy excoriates Bibi’s coalition with religious Zionists in no friendlier terms, and separately affirms the death of Gazan infants to be an ‘absolute metaphysical evil’. Yet he departs from split-blame narratives of the conflict by absolving Israel of responsibility for Gaza’s plight and conferring open-ended support to its security establishment, contrasting the strip’s incomparably lower civilian death toll with the 2016–2017 anti-ISIS battles of Mosul and Raqqa. Triggered by terror attacks in Europe that claimed far fewer lives than October 7, the world shared the ‘moral burden of war’ with the US and France far more equitably in those cases—despite far ghastlier collateral harm on the ground in Iraq.

Lévy was busy drumming up Western support for Ukraine when he landed in Israel on 8 October 2023, on the trip that sparked the book, and keeping alive his two-front case for a war-ready liberalism has become no easier since. Yet he posits his experience of remote crises and far-flung conflicts—from Kurdistan to Bosnia to Darfur—as a ‘red pill’ against the Western media’s anti-Israel slant. He claims to have ‘no lessons to receive’ from those who did not echo his calls in every past milestone of his peripatetic writer-activist career—even as many of those movies, tracts, and plays often turned out to be box-office flops, for reasons unrelated to the righteousness of their subject.

‘Lévy can be located on a four-way partition of Franco-Jewish political identities, where a conservative–progressive spectrum intersects a dichotomic affirmation of Jewish identity tested by the urge to assimilate’

Although still committed to mediated or yielding solutions to the Palestine question, Lévy is also well placed to factor past failed attempts into the current calculus. He recounts being commissioned to draft a peace plan by Dominique de Villepin in the wake of Oslo’s failure—later binned, per French ministerial custom—on the basis of a speech he gave in Tel Aviv for a pre-emptive ‘dry peace’ instead of endless peace-seeking talks susceptible to being derailed at any minute. Then-Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon confided to Lévy that a unilateral withdrawal from Gaza, to be carried out in 2005, was to be a prelude, he hoped, for the same retreat from the West Bank, manu militari. Lévy endorsed Sharon’s hopes that a civil authority would take over and channel worldwide help into building a prosperous embryo of a state along the strip. His book—and the exasperated bitterness at the Palestinians it mutedly conveys—proves that one’s pro-Israel stance can remain loyal to liberal internationalism even as what was never a good-faith partner turns into an even deadlier foe.

Lévy excoriates, mind you, the settling impetus of religious Zionism. Yet given post-2005 Gaza proved the opposite of the hoped-for prelude, he eschews calling for the dismantling of existing settlements in Judea and Samaria. Even as he remains committed to someday returning land seized in 1967, he excoriates the notion that ‘settler colonialism’ is the ideology that underpins Jewish statehood, and instead partly falls for the progressive flipside, defining Zionism as ‘a form of anti-imperialism’. The notion seems traceable to his first dispatch from Israel, in 1971, a piece2 equating Israel and Palestine’s yearnings for self-rule as comparable forms of ‘Zionism’.

This argument points by omission to the core of Lévy’s liberal belligerence. Though separate from previous war calculi, he backs Israel’s current effort perhaps aided—not hurt—by viewing zero-sum conflicts over land as only an unfortunate by-product of Palestinian leaders’ refusal to accept a two-state solution. He hopes that victory will not be followed, in other words, by further ‘land seizures’, but remains unperturbed if they do, as their self-inflicted nature in the arc of Palestinian rejectionism remains evident, despite the surge in settlements. Lévy even hints at a war of liberation in Gaza. He longs for a Palestinian version of West German President Richard von Weizsacker, who claimed that the bomb-induced defeat t Allied hands in 1945 proved a blessing for his country—thus at some level indulging the temptation, convenient yet treacherous, of Nazifying Hamas.

Lévy speaks of victory as a Jewish ‘duty’, and of the UN’s hands as being ‘bloodied’ for undermining Israel’s calls to evacuate Gaza. Indeed, he even makes a loaded reference to Amalek, the biblical archenemy of the Jews. Judaism’s place in Lévy’s liberal Zionism is characterized by an often-instrumental nature in arguments most would associate with his Orthodox, or halachic, opponents. The ‘liberals resembling Israel’ of his biblically infused binary are universalists wishing Israel would uphold the best in mankind, a duty that Lévy goes out of his way to re-root in religious commands to repair the world. Though the exigencies of self-defence do not supersede this injunction, the duty to combat discrimination that Lévy entrusts to Judaism paradoxically yields to liberalism instead as the central moral agency of his ethics. Democracy, he writes, is ‘the least bad profane translation of the adjuration that Israel remains a just people’. His Zionism is ‘radiant, luminous, exemplary’. Anchored in faith, Lévy’s run-of-the-mill liberal shibboleths insinuate that for any other outlook to seek to ground itself in the Hebrew Bible would amount to blasphemy in his eyes.

But for this smuggling of scripture in political form, Lévy would sound like typical legacy liberal-Jewish institutions in France and the US, such as the Conseil Représentatif des Institutions Juives de France (CRIF) or the Anti-Defamation League (ADL)—and just as oblivious to shifting sensibilities among Jews in both countries. It is Lévy’s description of Zionism’s other face, the ‘illiberals’, that is more original. He lumps right-wing Jews and the pro-Israel gentile right in that category, with both gate-kept out of Zionist respectability. He goes as far as to equate the former to a blood-and-soil, Caanan-like version of Judaism, while urging Jews not to trust pro-Israel nationalists in Europe and the US. Even as he stresses the world-altering evil of October 7—an evil that has ‘resumed History’s motion, disproving Sunday Hegelians’—he allows for no share of Israel’s new friends to come from a sincere reaction to the horror.

‘Lévy deserves credit for standing between a war he deems just and “pro-Israel” liberals abhorring the state’s present rulers’

Lévy leaves France largely unaddressed—perhaps a result of declining familiarity amidst constant world touring—yet this maelstrom nowhere has starker overtones. He claims the legacy of the Israélites, a disused appellative for ‘Jew’ connoting the assimilationism that predated Ashkenazi waves of migration to France in the late nineteenth century. Unlike the latter refugees from tsarist pogroms, these French Jews would also later be largely spared deportation by the Vichy regime. The kinship Lévy signals is with the fusion of liberalism and assimilationism this Jewish elite embodied. Their mores secularized a religious ethos into French republicanism, thus turning Jews into the vanguard of human rights, to the cradle of which—France—they owed their emancipation. Lévy revives this secular faith when claiming that October 7, via its violence on Jews, amounted to an attack on humanity itself. This liberal-universalist conviction in him has survived the ‘absolute evil springing from the gates of hell, triggering a shout of fright through the echo chamber of centuries’. The massacre shook every liberal bone in Lévy’s body, breaking none.

His place in French Judaism is unstable, though. The liberal republicanism inspired by Jewish ethics, awakened by the late 1890s Dreyfus Affair, frayed when post-colonial migration in the 1960s imported into France a conflict with Islam that put Jews in the crosshairs. Dwarfed by the nearly five million current residents descended from the mostly Muslims who migrated for work post-war, around 235,000 non-Ashkenazi Jews fled the newly independent Maghreb to France, too, from 1948 to 1967 (half of them have since made Aliyah, the decision to live in Israel). Born in Algeria, whence most of these Jewish pied-noirs hailed, Lévy sits above a community torn. Inheriting part of his father’s fortune propelled him to elite Franco-Judaism, a vantage point from which he witnessed the fraying of the Sephardic, Mizrahi, and Judeo-Berber grassroots. Lévy’s turf overlaps with the CRIF, the umbrella group bridging pro-Israel stances with French state values. While long a magnet for anti-Semitic bile, the CRIF is also losing the trust of Jews less favoured than Lévy, who are joining a wider French antipathy towards elite institutions of any kind.

Lévy can be located on a four-way partition of Franco-Jewish political identities, where a conservative–progressive spectrum intersects a dichotomic affirmation of Jewish identity tested by the urge to assimilate. All French Jews inhabit one of the quadrants, though they may move across them over a lifetime.

Even as they worship alongside and remain engaged, identitarians of the right and left are increasingly at odds over the viability of a full Jewish life in today’s France. The former are perhaps best embodied in politics by Bibi’s man in France, Meyer Habib, whom his constituency of expatriates in the eastern Mediterranean, including Franco-Israelis, failed to re-elect as MP in July 2024. These Jewish exiles—having deserted one diaspora only to begin embracing another—have long felt abandoned by a state too indulgent towards Islamic Jew-baiting and double standards of permissiveness with Islamic encroachments on the public square. The latter bloc, meanwhile, would like the long-settled Jewish acceptance of that secularist compact (laïcité) prolonged. With progressive Judaism easily shading into assimilation in a France that traditionally champions both outlooks, liberal identitarians are fewer and fewer in number, striking even gentiles as naive. Yet it is this narrow category that Lévy often occupies—and even speaks for—in his world-touring career, while nodding to the French state’s claim of superiority over the Torah back home.

Assimilationism, meanwhile, is less binding. The Sephardic acquaintance with Islamic Judeophobia inclines it towards the right, though identitarian Zionism has not fully channelled all that antinomy since the 1990s, when the mass Franco-Jewish exodus to Israel began. Some who remained in France, in fact, wield that very French identity as the bulwark against an Islamism they deem menacing to France itself, a stance best captured by presidential aspirant Éric Zemmour. While these assimilated Jews may have held their more identitarian co-religionists in contempt, these days it is elite liberal Israélites such as Lévy that they are most alienated from. Even when sharing assimilationist inclinations, the French identity the two groups claim to uphold has ceased to mean the same thing. What families like Zemmour’s acculturated into in the 1960s, often Frenchifying their names, is a vision of France deemed an ethno-Gallic reactionary distortion by sermonizers like Lévy.

‘Lévy’s anguish at Israel’s solitude will, by then, seem warranted’

Add in the fuel of class—Zemmour often speaks for middle-to-lower-class Jewish families who could not afford flats in the wealthy West of Paris when the banlieues became unliveable—and this amounts to an unprecedented realignment. The bridging of the Jewish right across old identity chasms and against uppity liberal Jews overpowers either bloc’s inner divisions on Israel—not to mention the former’s reunion with the increasingly pro-Israel gentile right, notably the heretofore-toxic Rassemblement National of hereditary Le Pen fame. Assimilationism thus loses some of its binding potency in favour of newer nexuses of alliance building—a trend that curiously may end up further melding Jews into gentile political currents.

Digressions of this sort would be more relevant if only Lévy did not shirk from addressing Israel’s survival as interlocked with pan-Western challenges. Yet the only relevance he lends to the Jewish state beyond itself is the mission of reviving the hubristic liberalism of end-of-history legend. He potently rebuts liberalism’s anti-Zionist drift, to be sure, but without framing anti-Semitism as an affront to any other set of principles. He thus wholly misses, to the point of deeming illegitimate, the deeper civilizational wellsprings that pro-Israel non-liberals see as threatened by both Islamic terror and mass migration to the West. Lévy eschews common cause with this growing constituency, even as it has proved, since October 7, least shy to confront the threat of multiculturalism and broken multilateralism on the safety of Israel and the diaspora.

The support shown by post-liberals for Israel is a bias Lévy returns in kind, by writing off judicial reform, religious Zionism, and Judaism’s strengthened role in the Israeli public square as a theocratic perversion of the one true liberal Israel. Both sides, for good or ill, are racing for a hilltop to build their city on. And despite the war, the struggle over Israel’s ideological direction seems at times more zero-sum than in other nations, with liberalism also at stake.

Lévy is ultimately boxed within the same pre-October 7 suppositions that paralyse legacy Jewish institutions cornered by anti-Zionist Wokeism yet unable to broaden their appeal or become agents of larger coalitions. More familiar in Ukraine, his battlefront liberalism is necessary and original in Israel. Yet standing on those same rigid principles blinds Lévy to the prospect that, abandoned by liberals, Jews will either find new allies or perish as a sovereign entity capable of self-defence. His book admirably re-grounds a battered case on an ideology that was crucial to its initial success, before quickly abandoning it. Yet forswearing a pathway of political viability with a coalition differently inclined, whose fortunes are rising across the West, risks isolating Jews of all persuasions in the long run. Lévy’s anguish at Israel’s solitude will, by then, seem warranted—but also self-inflicted.

NOTES

1 Bernard-Henri Lévy, Israel Alone (Wicked Son–Simon & Schuster, 2024), 176 pages.

2 Bernard-Herri Lévy, ‘Sionismes en Palestine’ (Zionisms in Palestine), Éléments (4 January 1971), bernard-henri-levy.com/fr/sionismes-en-palestine.

Related articles: